More than 2,000 confirmed COVID-19 cases are missing from the map the City of Toronto released last week that shows infections by neighbourhood, CBC News has found.

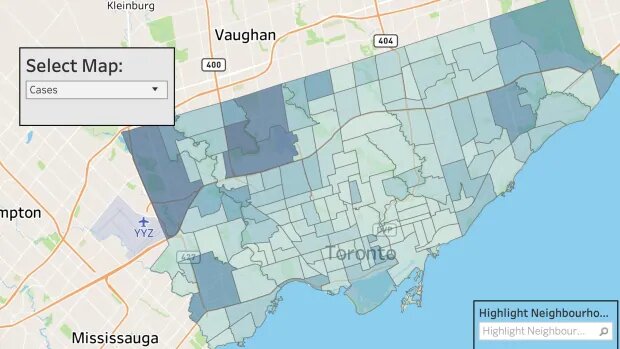

The detailed geographic information about the spread of the novel coronavirus was released last week by Toronto Public Health, marking the first time such data has been made available in Ontario during the pandemic. It shows infections based on where patients live.

But in a review of published data, CBC News found the count on the map comes up short.

On Thursday morning, the map, which is updated daily at 3 p.m. ET, showed 9,623 positive COVID-19 cases distributed over 140 neighbourhoods. That’s 2,029 cases short of the official 11,652 total count for that day.

That means roughly one out of every five cases is missing in the city’s own geographic analysis. Similar proportions of missing data were found in the map and case counts from previous days.

The data gap was not mentioned in any of the local health authority’s statistics or on its webpage until CBC pointed it out.

An extra row identified as “Missing addresses/postal code,” totalling 2,029 cases, has been added to the city’s downloadable spreadsheet showing the number of cases assigned to each neighbourhood.

Toronto Public Health blames the missing data on reports sent by testing labs. The public health authority says some forms only have a name and an address, while others don’t have a patient’s postal code or phone number, leaving health authorities scrambling to fill in gaps.

“Sometimes, they are not putting enough contact details, and in the legislation it doesn’t specify that you must include XYZ details of the individual,” said Dr. Vinita Dubey, Toronto’s associate medical officer of health, referring to the provincial law that requires medical labs to report positive results of certain tests to local health authorities.

“It just requires that it be reported, so that’s where some of the missing information and gaps occur.”

Delays possible

Dubey said it’s “very unlikely” that the missing data had an impact on contact tracing, but that there could have been delays as her staff had to retrieve missing contact information before they could connect with a patient who tested positive.

Toronto Public Health said that so far, it has been able to complete contact tracing for a patient within 24 hours in 88 per cent of cases.

The issue of information transfer between laboratories and public health units was raised last Friday in a report to city council and the Toronto Board of Health by Toronto Medical Officer of Health Dr. Eileen de Villa.

“Laboratories’ reports are received all together in one large fax, sometimes containing hundreds of individual lab results, which must be taken apart for further processing,” de Villa wrote.

She called for changes in laboratory procedures and the provincial law.

Missing hot spots

Beyond potential delays in contact tracing, the missing geographic data might have another impact.

Toronto’s current map distribution suggests that some of the city’s poorest and most diverse neighbourhoods — predominantly in the northwest and northeast areas — have had the highest number of cases so far and might be most vulnerable to the novel coronavirus.

As Ontario is ramping up testing, resources like mobile testing clinics, staff and personal protection equipment will be focused on those hardest-hit areas of the city.

But with 2,000 cases missing, one researcher familiar with Toronto’s map data said health authorities could be missing out on other vulnerable communities.

Kate H. Choi, an associate professor in the department of sociology at Western University in London, Ont., said Toronto has been ahead of the curve in terms of COVID-19 data collection, so she was “really, really surprised” when she was told how many of the city’s confirmed cases were missing from its map.

She said part of the issue might also be that some populations are less likely to be able to provide a precise address or a postal code, including homeless people, migrant workers or nursing home residents.

“We may be missing COVID-19 hot spots or certain vulnerable populations may be missing from the narrative about COVID-19 in Toronto.”

Alternatively, some Torontonians might feel a false sense of security after assuming their neighbourhood is low-risk based on the map, said Choi. It’s also possible that resources and staff could fail to be deployed to hospitals in unknown hot spots, which could lead to more transmission of the virus.

“Those 2,029 individuals are someone’s loved one,” said Choi. “They are also 2,029 people who could be your neighbours. They could be residents in an area where there are a lot of asymptomatic carriers and unfortunately, that may mean they could bring COVID-19 to your doorsteps.”

WATCH | Toronto releases a map showing the city’s COVID-19 cases:

Choi stressed that more research on the age, gender and other characteristics of the missing 2,029 cases is needed to fully understand the impact and risks of this data gap.

Toronto Public Health has also repeatedly said that the map shows where patients infected with COVID-19 live and not where they acquired the infection.

Gap won’t be fixed for weeks

Toronto Public Health said it does not have the resources to go looking for the 2,029 missing postal codes at the moment.

“Some of them were early on in our outbreak and so it would require going back to some of these cases in February and March. That work won’t be done until we either have less cases or have reached the end of the first wave,” said Dubey.

This is the second data gap uncovered by CBC in less than a week. On Monday, it was revealed that Ontario hospitals had failed to flag 700 positive COVID-19 tests to public health officials because of a mixup.

In a statement to CBC, Ontario Health has said the impact of the error “may not be fully understood for some time.”

Source link

Be First to Comment